Last week, media scholar Casey McCormick posted a piece at Flow—where I have also been contributing during this most recent cycle—based on her research into Netflix, with a specific interest in the way they tell stories. I saw her present some of this research last week, and at the heart of it is an interest in what she terms “Netflix Poetics.” While this can take many forms, at Flow McCormick narrows in one element wherein many series “tend to be particularly metafictional, or self-conscious about storytelling,” citing the use of voiceover or direct address in shows like House of Cards or Narcos.

Last week, media scholar Casey McCormick posted a piece at Flow—where I have also been contributing during this most recent cycle—based on her research into Netflix, with a specific interest in the way they tell stories. I saw her present some of this research last week, and at the heart of it is an interest in what she terms “Netflix Poetics.” While this can take many forms, at Flow McCormick narrows in one element wherein many series “tend to be particularly metafictional, or self-conscious about storytelling,” citing the use of voiceover or direct address in shows like House of Cards or Narcos.

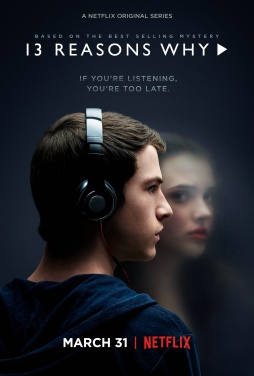

I was thinking a lot about the idea of “Netflix Poetics” as I watched 13 Reasons Why, Netflix’s most recent drama series, and the second this year that we could call “Young Adult” programming after A Series of Unfortunate Events. But whereas that series adapts a dark but ultimately whimsical set of children’s books, 13 Reasons Why—developed by Brian Yorkey with Tom McCarthy as the director of the opening episodes—taps into the very real tragedy of Jay Asher’s novel about a teenage girl who commits suicide, and the tapes she leaves behind to call out those she holds responsible. Channeling the type of issue-focused storytelling that’s characterized shows like Canada’s Degrassi, and which emerges more sporadically in teen programming on U.S. cable channels like MTV and Freeform, 13 Reasons Why offers an unflinching consideration of the social problems that would leave someone like Hannah Baker to take their own life.

I have a lot of thoughts about 13 Reasons Why, but more than any other Netflix series all those thoughts are caught up in the fact that it is a Netflix series. Based on both the narrative it presents and the way it chooses to tell that story, both the good and the bad of the show feel inseparable from the context of its distribution. It is a show that feels like it might have only been able to do what it does on Netflix while simultaneously feeling like it encapsulates some of the pitfalls of the rigidity of the Netflix model and its associated expectations. It is a show that is brutally honest about the struggles teenagers face today in ways that are refreshing and important, while simultaneously positioning itself to appeal to the cynical binge culture that Netflix increasingly relies on its original programming to construct.

It is also ultimately very good, and well worth your time, but I want to focus on how it represents a meaningful case study of the distinctiveness of Netflix’s original programming on the level of both the text itself as well as its distribution.

[The following will contain light spoilers for the entire first season of Netflix’s 13 Reasons Why.]

In what Alan Sepinwall identifies as a shift from the book in his review of the show, Clay Jensen goes through Hannah Baker’s tapes very slowly. It’s a choice that allows the show to structure itself around the tapes, with one episode for each, but as Sepinwall notes this creates a problem: reflecting on the fact other characters who had the tapes before Clay question his lack of haste, Sepinwall argues his slow pace “never makes emotional sense, despite Clay’s protestations that it’s too difficult to binge the tapes in the way that Netflix assumes you’ll binge the show.” And there’s no question the thematic connection is hard to miss when you’re binge-watching a show about tragedy—I went through the first season over a 24-hour period beginning Friday evening—as a character onscreen expresses his inability to binge-listen to the same story in the same way as his peers (a concept that seems culturally relevant given the recent all-at-once distribution of true crime podcast S-Town).

The resulting impact, though, is a fascinating engine to encourage the audience to invest in this story. Within the show itself, you have a group of characters—specifically the eleven people who had the tapes before Clay—who already know the story. Clay might be moving slower than the audience, but his function as audience surrogate reinforces the need for the audience to uncover what the majority of the other characters already know, and which we know they know. You are constantly reminded that each of them are taking on a defensive posture after having been exposed to the tapes, their every action fundamentally shaped by the fact that they were one of the reasons why Hannah killed herself. While the central “mystery” of finding out the full story of Hannah’s suicide is the central narrative engine, these ancillary characters become their own engine by way of their possession of knowledge the audience doesn’t have: binging the show is a matter of trying to even the playing field, able to interpret each character and not just the “plot” unfolding in the series.

I concur with Sepinwall that the show struggles to justify the fact that Clay moves slower than the audience, although there is some scaffolding put in place regarding past struggles with mental health and panic attacks that provide at least some justification. I’d also agree with Sepinwall that some of the middle episodes struggle to find story to tell around some of these characters, while others like Clay’s friend Tony are stranded for too long unable to explain themselves, and left looking like they are being withholding with no clear justification. In general, however, the show works overtime to ensure that the audience will want to know more, even when that knowledge comes with heavy themes and disturbing realities of contemporary teen experience.

The general consensus is that the middle episodes show some of the perils of Netflix’s general rule of requiring thirteen hour-long episodes, and I agree with this, but I would ultimately argue that any of the negative effects of Netflix’s season structures—like episode length bloat—are offset by the fact that 13 Reasons Why never pulls any punches. Shows like The Fosters, Switched at Birth, and Sweet/Vicious have all done storylines that deal with issues of abuse and sexual assault, but those shows must balance these storytelling with the expectation that the shows will also appeal to the target demographics of their channels, and specifically the advertisers who represent the demands of ad-supported cable programming. For every storyline The Fosters did that struck me as important or meaningful, there was another that seemed sensational, ABC Family/Freeform needing the show to create drama-filled cliffhangers that they could put in ads to air during Pretty Little Liars. This does not discredit the shows and their efforts to shed light on meaningful issues, but it nonetheless detracted from them, and showcased the limits of commercial broadcasting in this respect.

There are elements of 13 Reasons Why that move toward more typical teen television storytelling, but it never fully abandons Hannah’s story in order to explore them, linking every character’s actions to the aftermath of Hannah’s death. When the show gets to its depiction of sexual assault, the camera does not pull away, continually returning to those images as they weigh on the characters involved. Content warnings precede these episodes, as well as the finale, which goes a step further and shows the act of Hannah’s suicide without cutting away, creating a series of truly alarming images that are going to be burned in my mind for an incredibly long time.

While Netflix’s lack of standards and practices allows the show to be “realistic” insofar as having the characters swear, the choice to show so much of Hannah’s suicide is more than this, part of a larger effort to portray some of the visceral realities of these situations that are often only alluded to in media depictions. There is no slow-motion to dull the impact of Hannah pushing the razor blade into her wrists, nor is there an intense musical score to dull the pain of seeing her parents trying and failing to revive her when they find her body. The show uses the lack of regulation on Netflix to show us something that I’ve never seen on television before, capturing the pain and horror of suicide in real time.

I am resistant to narratives that Netflix is actually “revolutionizing” television, given how similar most of its content is to what is offered by premium and basic cable offerings. But teen television is notably something that its biggest competitors have shied away from: HBO and Showtime have never really explicitly programmed to teens, given that they lack the disposal income to purchase subscriptions to their respective services and likely don’t control cable-buying decisions in their household. And while Hulu acquired webseries East Lost High, a show built on the DNA of Degrassi, its approach to social issues is to embed them within a more traditional teen soap opera, an effective method of alternative education but not necessarily pushing the boundaries afforded by its position (in part because of Hulu’s continued dependence on advertiser support, one imagines). Degrassi itself, meanwhile, still airs as a commercial broadcast in Canada despite appearing on Netflix in the United States, meaning it doesn’t have the same leeway to be explicit in its depictions of rape or suicide.

Netflix’s marketing of 13 Reasons Why, perhaps unsurprisingly, doesn’t always highlight this part of its storytelling: the main trailer, released a month ago, frames the show as a mystery thriller, largely ignoring the issues of the series in favor of framing this as an action-packed, must-see, rollercoaster of a television show. While all of those moments do appear during the series, I was struck watching the trailer—which I hadn’t seen before—how many of those moments played out differently in context. Rather than being “edge of your seat” moments, most are clear byproducts of the way grief and regret build up in the characters as they’re forced to hold onto these secrets. The show never builds “suspense” in the way the trailer does, even when it does get to unmasking its “villain”—or “villains”—at the season’s conclusion.

But while Netflix’s primary marketing may be obscuring its issues-based messaging, Netflix is nonetheless investing in paratexts highlighting this approach. A featurette released in mid-March is heavily focused on the “importance” of the show’s storytelling, with actors and producers reflecting on their pride in its potential impact and ending with suicide prevention contact information. And when I eventually reached the end of the show’s season, I was surprised when my Netflix continued to auto-play into a 30-minute featurette—“13 Reasons Why: Beyond The Reasons”—where the cast and crew, along with executive producer Selena Gomez and the experts who served as consultants on the show, went through the season’s story arcs to reflect on the issues presented.

The choice to have this bonus content play automatically upon completing the season is notable: I can’t think of another Netflix show where this has happened, and it shows an intriguing use of the distinct nature of Netflix distribution. By using the flow of “auto-play” in this way, Netflix presents the show’s educational function as part of the show itself—while some might immediately stop the feature from playing, and it does not appear as a formal “episode” of the show (buried instead in the “Trailers & More” tab), that most viewers will be presented with it in the moments following the show’s conclusion is nonetheless meaningful outreach and highlights the show’s strength in this area.

On social platforms (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram), Netflix balances these two approaches—while all 13 Reasons Why accounts are focused on teen-centric content focused on characters, romance, and social media use (including some in-world diegetic social media postings), the Twitter account also posted a video with stars Dylan Minnette and Katherine Langford discussing how important the book was to them, and their focus on telling this story properly given the weight of the issues involved. The 13 Reasons Why social accounts aren’t heavily pushing the type of issue-focused content present in “Beyond The Reasons,” but such content has nonetheless been present across platforms, whether through a link to the show’s resources webpage in their Instagram bio or in Crisis Textline integrations into the Instagram feed itself.

As a text, 13 Reasons Why does an impressive job of highlighting these issues in its own right. Anchored by tremendous performances from Langford as the girl who died and Minnette as the boy reliving her death, the level of execution allows for these issues to be taken seriously, and keeps them from feeling like “lessons” sitting outside of the text. Although I may have been surprised by the bonus feature playing immediately after the finale, it was not as jarring as you might expect, as its honest and serious approach to the issues at hand was building on what came in the show before it. Despite reservations about some of the storytelling introduced to flesh out the narrative, the core values of this story are incredibly strong and powerfully brought to life, and have the potential to make a significant impact on young viewers who may be used to a more sanitized portrait of situations like the one facing Hannah here.

However, for as much as the show demonstrates some of the benefits of the Netflix model, its ending also highlights some of the pitfalls. Although Netflix’s distribution model theoretically allows for shows to deviate from the traditional broadcast business model of producing as many episodes as possible in order to profit from secondary markets, the Netflix business seems to push back against shows that are explicitly designed to run a single season. While Netflix’s model may not be pushing shows to do a full 22 episodes, it is dependent on shows running multiple seasons, as it encourages subscribers to stay subscribed in anticipation that the show they connect with most will continue at some point in the future. A miniseries or limited series that has a closed-ended story may fill a hole in Netflix’s larger schedule, but it carries no long term potential in retaining the audience it focuses on, requiring them to develop entirely new series in that area, which may fail to connect in the same way. Given that Netflix has never canceled a show after its first season, there is a standing expectation that they will want more of a show if it serves any particular constituency of subscribers, an expectation that was likely communicated to the show’s producers.

Because of this, 13 Reasons Why has a frustrating ending, bending itself to create loose threads despite such a clear and impactful conclusion to Hannah’s story. While it registers as a thematic conclusion, and thus avoids feeling outright unsatisfying, the choice to leave clear cliffhangers—specifically through the characters of Alex, Tyler, Mr. Porter, and Bryce—reads as a forced edict from Netflix and the show’s producers at Paramount Television to leave the door open to make more. I don’t know how you could reasonably continue the show without Hannah and Clay’s story to anchor it, given how central that device is to its storytelling. That show feels like it would have significantly less impact, and struggle to be able to focus on issues rather than falling into a series of teen drama tropes to try to create enough narrative engines to make it feasible.

13 Reasons Why is important television, worthy of recognition both for a story invested in real issues facing teenagers and for its commitment to highlighting those issues in spaces outside of the text itself. However, it is important television that reinforces that Netflix is not a space where creators enjoy absolute freedom: for as much as some of the affordances of the Netflix model help make 13 Reasons Why so meaningful, other parts of the model manifest in the text in more cynical ways, and force it into a conclusion that risks undermining its strengths should it be brought back for a second season it may not be able to manage.

Cultural Observations

- While Kate Walsh and Brian D’arcy James have the more emotionally complex roles as Hannah’s bereaved parents, and are excellent, I really appreciated the more subtle work of Josh Hamilton and Lynn Hargreaves as Clay’s parents, who have to do more subtle work figuring out how to react to their son’s sudden change in behavior.

- Clay’s cut on his forehead is primarily there as a way to immediately distinguish between present Clay and flashback Clay, I realize this, but the idea that he didn’t get stitches given the size of that gaping hole in his forehead severely bugged me throughout the early episodes, in particular.

- I appreciate the verisimilitude of the brief webcam chat we see early in the season, as well as some nice sound design work when we see Hannah in the theatre booth from her perspective (with Alex and Jessica’s voices muffled) and from Alex and Jessica’s (with her voice muffled). The attention to detail was good throughout, but that was a particular highlight.

- While I don’t mind short auto-play windows when I’m working my way through a show quickly on Netflix, I do get a bit frustrated when there’s a great credits song like “Love Will Tear Us Apart” and I’m pulled away from it after three seconds.

- As a former socially awkward teenage boy myself, I definitely connected with Clay, although the choice to have him be someone who leaves the keyboard noises on when he’s texting did risk alienating me from him. There is also a moment later on that suggests he has the most singularly terrible “gaydar” in existence, which was also not a good look.

- Although there are plenty of “f-bombs” and other swearing, the show notably avoids any type of frontal nudity—the depiction of sex is explicit without seeming graphic, and what nudity we see is obscured by shower curtains and done more to showcase vulnerability than skin.

- The focus on the school administration brought to mind the second season of ABC’s American Crime, which was similarly explicit in its engagement with sexual assault, but also had to serve a larger number of storylines, and felt less anchored in personal experience as opposed to institutional observation. It’s a very good season of television, and available on Netflix as a depressing chaser to what we see here, but doesn’t pack quite the same emotional weight due to its scattered storytelling.

- Despite the warning that should have prepared me, the finale’s depiction of Hannah’s suicide and its aftermath turned me into an emotional mess, for the record.